Who: Alexandra Festila, festila@badm.au.dk , Polymeros Chrysochou, polyc@bamd.au.dk

What: What are the underlying cognitive processes that influence consumers’ perception of health, and how can a better understanding of these processes improve package design to better communicate healthfulness?

How: A set of communication experiments will be conducted in order to address the objectives of the study. The experimental stimuli will consist of mock-ups of hypothetical package designs of food products, varying the classes of package design elements (informational, visual, structural). The specific elements and their levels will be chosen based on a previous study (a content analysis of food packages). In the experimental conditions, the degree of typicality (or congruency) of the packages will be manipulated. Further, the cognitive response to the various conditions will be assessed, at different levels. One level refers to the inferences consumers make about the product, and the brand, based on the package design cues (e.g. perceived healthfulness). A different level of cognitive response is the subject’s felt fluency of the package design. Processing fluency, or the subjective experience of ease with which people process information, further influences consumers’ judgement across many instances (e.g. liking, truth) (Alter & Oppenheimer, 2009; Schwarz, 2004). As such, it might also act as a mediator of the relationship between package design and consumers’ response (Chae & Hoegg, 2013; Sundar & Noseworthy, 2014), an effect that will also be addressed in the study. Further on, certain moderating factors will be accounted for. Possible moderators are the type of consumer (e.g. if the consumer has a health goal) or the context (e.g. vice versus virtue food categories). Hereby, it should be possible to determine how internal cognitive processes relate the communicative message of healthfulness conveyed e.g. through the symbolism and semiotics of food packages.

Why: The topic is both timely and important as it addresses the current trends and societal needs for healthier food choices. The rising public concerns about overeating and unhealthy diets have highlighted the importance of package design for public health and marketing (Orth & Malkewitz, 2008; Wansink & Chandon, 2014), given that in most of our everyday food related actions (i.e. from shopping in store until consumption at home) we interact with package design. It is thus inevitable that package design has a significant role in influencing consumers’ food related behaviour. Understanding the underlying cognitive mechanism that influence healthy food choices – such as processing fluency – can be used to inform package design, and thus significantly improve the way healthfulness is conveyed and communicated to consumers. Additionally, it would shed light on the different “traps” consumer might fall into when going for the “healthy option” and possible ways to avoid them.

What’s next: The data collected through the experiments will enhance a collaboration potential with the Food and Brand Lab (FBL) at Cornell University, where I’m planning a research visit in the fall of 2015. FBL is led by Prof. Brian Wansink, who is a very well established marketing scholar with a high publication record on topics of health communication and nudging. Prof. Wansink’s publications have appeared in several high-esteemed journals (e.g. Journal of Marketing, Journal of Consumer Research) and he is also the author of two books (Mindless Eating, and Slim by Design). During my research stay at FBL, I plan to collaborate with Prof. Wansink in writing-up the results from my studies and work on potential publications.

Key references:

Who: Andreas Lieberoth, andreas@psy.au.dk, Panos Mitkidis, Jacob Friis Sherson, CODER center will match IMC-seed

What: Does framing economic behavior games as “real” games through instructions and digital design influence cognition and social economic behavior?

How: We want to make an online game interface for econ games. Subjects will play in multiple conditions (two in pilot, then factorial in main study) comparing serious/utility-oriented versus playful/game-oriented presentations. The gamy framing is suggested to establish a paratelic metamotivational stance, or magic circle which may influence experiences of the situation and resulting behavior.

Outcomes will be tested on two fronts:

1.) Engagement measured with self-report and self-directed behavior measures (standardized intrinsic motivation setup) to test the hypothesis that framing has motivational psychological effects (as found with social board games by Lieberoth, 2014).

2.) Economic behavior to test the hypothesis that a gamy framing will lead to either more competitive/self-serving behavior (disregarding the cost to others due to magic circle) or less risk-averse more experience oriented behavior (disregarding cost to self due to magic circle, making room for others to succeed to preserve game experience).

Potential mediators like personality factors and game preferences will be measured explanatorily. After the pilot study (N= 2x30, lab-based), a main study will be conducted online via on CODER’s www.scienceathome-platform. The interface will be adjusted based on initial findings.

Why: Digitalizes well-received findings (Lieberoth, 2014) which beg exploration in behavioral and digital domains. First steps in adding behavioral economy and social citizen science functions scineceathome.org, which will allow ongoing data-gathering and teaching resources.

Key references:

Who: Dan Mønster (danm@econ.au.dk), Joshua Brain (jbrain@econ.au.dk)

What: What is the quality of data obtained with the new Cortrium C3 device? AU Cognition and Behavior Lab recently purchased two Cortrium C3 devices that are compact, lightweight, low-‐cost wearable devices for measuring ECG, respiration, body (centre-‐of-‐mass) acceleration, and surface temperature (with other measures possible and planned, see Ref. 1). However, since the device is new it is unclear how data quality compares to equipment more widely used in research. We therefore propose a study to compare data from Cortium’s C3 to BIOPAC’s BioNomadix BN-‐RSPEC wireless ECG and respiration amplifier.

How: We propose a within-‐subjects design where we record data from all participants using both the Cortrium and the BIOPAC systems. Raw data recorded using the two devices will be compared, and derived measures such as inter-‐beat-‐interval and heart-‐rate-‐variability measures will be computed and compared. All measures will be recorded during three conditions: baseline (rest), physical activity, and mental activity.

Why: The results of the study will be important to other researchers at IMC and COBE Lab who use heart rate, respiration and acceleration data in their experiments. The Cortrium C3 has the potential of providing an easy and low cost method of recording these types of data in the lab and in the field. Obviously data fidelity is very important, and our study will provide a benchmark test. The Publication will add to DM’s and JB’s list of publications and promote the lab.

What’s next: We expect to publish the results of the study in Journal of Psychophysiology, International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications or a similar journal. Similar studies have been published for the Polar heart rate monitor and the Actiheart device (see Ref. 2–5). Depending on the results, we expect other researchers to use the device, and possible follow-‐up studies may be planned to look at more specific applications or other capabilities of the final C3 device.

Additional Comments:

The proposed study is small-‐scale and easy to perform. A female research assistant will be needed to fit the devices to female participants, and we have also added RA hours to help transfer and convert data from the equipment to a format ready for analysis.

Data analysis will be performed with the same software tools (e.g. Matlab with ANSLAB (Ref. 6)) for both the Cortrium and the BIOPAC equipment in order to avoid any difference in results due to different algorithms.

Key references:

Who: Dan Mønster danm@econ.au.dk; Simon DeDeo (Indiana U. & SFI)

What: Can we observe the emergence of political order under controlled laboratory conditions?

Recent avian studies [1] have demonstrated a complex interaction between (1) the microscale dynamics of conflict behavior and (2) coarse-‐grained social variables that summarize these conflicts as differences in relative rank. Individuals in this society of birds come to know these coarse-‐ grained facts about power in their society, and adjust their behavior in response to this knowledge. This feedback loop, between micro-‐scale decision-‐making and macroscopic social facts, is closed by cognition and perception at the individual level. The conflict—power loop may be a potential “model system” for the emergence of political order, comparable to the Prisoner’s Dilemma in studies of cooperation and altruism. We propose to extend the results to the human case, by studying ad hoc human groups. Are individuals able to perceive the conflicts around them as part of a larger struggle for power, and do they alter their behavior in response to this knowledge?

How: We propose a computer-‐based interaction experiment in which human participants can pick “fights” with other participants, and observe how this affects their own rank. If the feedback loop successfully engages, we will be able to observe the dynamical emergence of a top-‐down causal influence of an emergent, coarse-‐grained social variable. Individual choices will be increasingly guided, above well-‐defined null models developed in Ref. [1], by facts about rank. We will consider various conditions, with the critical variable being the extent to which participants are made explicitly aware of their rank. In the base condition, participants can observe their own rank, and the recent behaviors of all other participants, but not the other participants’ ranks. Extended conditions may involve increasing amounts of social-‐level facts; repeated games; and the manipulation of subject populations (male/female/mixed/computer agents).

Why: This work provides a clear methodology which, if successful, will allow researchers to construct a “society in a box”, with well-‐controlled conditions that can be varied in different ways while allowing for direct numerical comparison between conditions. Success in our proposed work has the potential to provide a new window onto our quantitative and comparative understanding of large-‐ scale political order. The project will give DM the opportunity to work with SD and learn new analytical tools; it will further connect IMC to both Indiana University’s Cognitive Scientists and the wider community of the Santa Fe Institute; it will provide new points of contact for SD with the IMC and AU, and training for SD in behavioral economics.

What’s next: SD is preparing a proposal to the US Dep’t of Defense on the micro-‐to-‐macro map and the origins of political order.

Additional Comments:

The role of coarse-‐grained social facts in human society is clear even to a casual observer—we tell stories about our social world that simplify and caricature its details, and act on the basis of those stories [2, 3]. One of the clearest cases of this kind of top-‐down influence involves facts about power and prestige [5].

Uncontrolled and broad-‐spectrum experiments—where individuals interact through multiple channels, with a wide variety of perceptual information, and with a variety of symmetry-‐breaking initial conditions—are able to reproduce such top-‐down effects, sometimes quite dramatically as in the case of Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment.

We lack, however, an understanding of the minimal conditions under which political order might emerge. A positive result in the experiments proposed here—results in which we are able to detect the diachronic development of novel strategies in human subjects structured by overall rank—would provide one of our first direct comparisons between the origins of political order in human and animal sociality.

It would also provide a proof-‐of-‐concept for a simple methodology to test for the influences of various exogenous conditions on the formation of political structure. With base results in hand, researchers could test effects as varied as in/out-‐group manipulation, priming, gender, group heterogeneity and individual-‐level personality traits on the development of the feedback loop.

A negative result would still provide interesting data for individual-‐level decision-‐making in response to group variables. By increasing the amount of information provided to subjects, we may be able to get a “null result of interest” and would be forced to question these minimal accounts and to look to more culturally complex pathways.

A parallel may be drawn between our work and our understanding of cooperation. We see cooperation everywhere in the human social world; but our understanding of the nature of cooperation was immeasurably enriched by the invention of the minimal model Prisoner’s Dilemma game, and its extensions by Axelrod et al. [4] to the repeated interaction case.

Prisoner’s Dilemma allowed us to understand, for the first time, public goods games, to compare cooperation across cultures (where remarkable similarities can be observed) and across species (where we learned the extent to which cooperation is an essentially human phenomenon).

Cooperation, however, can be sustained by use of micro-level facts concerning individuals (reputation). Power, by contrast, is an essentially political phenomenon, depending on consensus beliefs about how to coarse-grain the actions of the group, and is one of the key transitions from two-‐person interactions to large-scale society.

Key references:

Who: Dan Mønster danm@econ.au.dk, Riccardo Fusaroli, Kristian Tylén.

What: Several recent studies have shown that people’s heart rates synchronize when they engage in social interactions [1–4]. However, the mechanisms behind this phenomenon are unclear. The purpose of our study is to investigate several proposed mechanisms. It is well known that heart rate is influenced by respiration (respiratory sinus arrhythmia) and movement. Both respiration and movement play roles in coordination during social interactions. Conversations, for instance involve complementary respiration due to turn taking and both synchronous (postural sways) and complementary (gesture) movement. The main purpose of our study is to detail the role of synchronous and complementary speech and gesture on heart rate coordination, in the context of both controlled and more naturalistic interactions.

How: We propose a 3×3 within-‐subjects design using dyads performing three tasks (speaking together, moving together, and doing a communication game together) in three conditions (synchronous, complementary, and externally driven). The speaking task (reading aloud) is designed to have a minimum of movement and in the movement task (following a shape with a pointer) there will be no speaking. The communication game has no restrictions on speech or gesture. In the synchronous condition the subjects will be instructed to perform the tasks as synchronously as possible, whereas they will take turns in the complementary condition, and finally in the externally driven condition they will perform the task following externally (computer) generated cues. Our measures are: gesture (using accelerometers), respiration and electrocardiogram (using BIOPAC), video and audio. The data will be analyzed using recurrence quantification analysis and convergent cross mapping.

Why: Several studies have shown synchronization of heart rates between individuals engaged in social interactions [1–4], but the mechanism responsible for the observed synchronization remains unknown and has not even been investigated. Without knowledge of the mechanism(s) it is hard to draw reliable conclusions and generate sound hypotheses for further studies. Our project can help put future studies on a more solid ground.

What’s next: We expect that our project will establish a more solid basis for the study of heart rate synchronization and thus enable better future studies of synchronization in groups. This will directly contribute to the coordination meta-‐ perspective of IMC, and sow seeds for studying cooperation. The goal is to present the results at relevant conferences (e.g. Jam and CogSci), to publish at least one article in a relevant journal, as well as our data and the code used for analysis in order to facilitate reproducible research. The data and code will be published on a data-‐sharing web site (e.g. figshare). We expect this initiative to generate additional citations and possibly result in new collaborations.

Additional Comments: This study received seed funding in 2014, but we were unable to use it because of technical difficulties in programming the stimuli. Software development assistance has now been added to the budget (DKK 6 000) which will be spent on a student programmer. The experiment will be conducted at Cognition and Behavior Lab, AU. All the needed equipment is available from the lab (BIOPAC, cameras) and from IMC (accelerometers).

Key references:

Who: David J. Hendry (david.hendry@ps.au.dk), Institut for Statskundskab

What: When people are asked to respond to attitudinal questions on sensitive social issues, how will they behave when they learn (1) that a group of peers holds an opposing view, and (2) that this group of peers will witness their responses? Furthermore, if people alter their expressed attitudes to conform to the responses of their peers, what is the mechanism underlying the change?

How: I will use a battery of attitudinal questions on sensitive social issues as an online pre-screening questionnaire for a set of experimental subjects. A subset of respondents will be invited to participate in a group-based laboratory session at the AU COBE Lab. Subjects will engage in interactions with others participating at the same time through a computer interface in which they are led to believe that their behaviors are visible to their fellow group members. At some point during the interaction, subjects will be asked some of the same items that they were asked on the pre-screening questionnaire after a group of their peers has responded in a way that is unanimously opposed to or unanimously in favor of the way that the subject responded initially. This allows for an empirical test of subjects’ propensity to conform opinions that differ from their own, with the computer interface granting researcher control over the responses of fellow group members. Following the group interaction, subjects will be asked to answer a post-laboratory questionnaire in which they will be asked the same set of questions that were asked in both the pre-screening questionnaire and the laboratory session. This allows for an empirical test of whether the mechanism underlying any conformity exhibited in the laboratory is durable or short term.

Why: This project is important to the career development of the PI because it will act as a proof of concept for an experimental paradigm that has not been used previously, with preliminary results used to bolster future research plans. It is important to the discipline because the internalization of rhetorical norms through interpersonal interactions represents a major empirical gap in the social science literature. It is important to the Centre because it represents an empirical examination of the effects of human interaction on choice in a context that has received a great deal of theoretical and anecdotal attention, but almost no rigorous empirical attention. The importance of this work to the broader world lies in its ability to speak to the mechanisms underlying the impact of social interactions on choice in a variety of important settings that are difficult or impossible to observe (e.g., juries, schools, workplaces, deliberative forums).

What’s next: I expect the results to be of interest and publishable in political science and social psychology. If successful, it will act as the basis for a larger funding application (FKK or EU Council) that will investigate in greater detail the conditions under which social conformity should and should not be expected with respect to social and political attitudes. It will be part of a larger project that brings together these laboratory results with historical research on changes in societal norms and a series of theoretical models of cultural evolution.

Additional Comments: Most broadly, the phenomenon motivating this work is that across the Western world, the twentieth century witnessed a reversal in rhetorical norms regarding equality between groups. Previously, it would have been common in various social circles to openly express the superiority of certain societal groups over others. But by the end of the twentieth century, this norm had reversed, and any public pronouncements of the inherent superiority or inferiority of certain groups would be met with strong disapproval, and could carry serious negative reputational consequences. A great deal of research has documented that these changes in expressed attitudes have in fact occurred, but the question of how people learn about and internalize these norms still lacks a rigorous explanation in the social science literature.

On salient social issues, people tend to be aware of whether there are norms of appropriate behavior that govern the range of socially acceptable expression (Crowne and Marlowe 1960; Kuran 1995). The major argument of this project is that mass awareness of these norms comes primarily through social interactions. Through interpersonal interactions, common knowledge of socially acceptable behavior exerts social pressure on individuals to act according to behavioral norms (Festinger 1954; Sherif 1936). In some situations, individuals may have a sense that there are truly correct and incorrect attitudes with respect to a given social referent, and that the attitudes of one’s peers serve as a benchmark for the appropriateness of certain opinions (Burt 1987; Kelley 1952; Levitan and Visser 2008). In other situations, peers serve as standards of appropriate behavior without regard to factual accuracy (Deutsch and Gerard 1955; Kelley 1952).

The particular type of social influence most relevant for this project is social conformity, i.e., the tendency of individuals to publicly comply with a known or perceived group opinion. Following Sherif (1935) and Asch (1951), a long line of research in social psychology has demonstrated that social conformity is in fact empirically verifiable in a laboratory setting. Using confederates to exert social pressure on subjects, this research has demonstrated that individuals can be moved far from what they believe to be the correct response to a question when they are compelled to state their responses publicly. However, this line of work has focused almost exclusively on arbitrary decision-making tasks that have no social significance for the subjects outside of the laboratory.

The impetus for my experimental paradigm is that this basic approach offers a powerful framework for simulating and experimentally manipulating the types of casual social interactions that are expected to be the primary vehicle for the internalization of rhetorical norms. Any differences between individuals’ private opinions and what they are willing to state publicly can potentially be leveraged in an experimental setting, with the computer interface allowing for researcher control over the responses of subjects in a group setting. In this way, participants simultaneously play the role of confederates and subjects. In these computer-mediated group interactions, I predict that there will be a strong tendency to move away from one’s own privately expressed opinions when a group of peers unanimously expresses an opposed opinion, and when the subject believes that her responses will be publicly visible. Furthermore, I predict that these changes in expressed attitudes represent temporary public compliance with the group opinion, without actual internal attitude change. If this prediction is correct, one important implication is that large-scale changes in rhetorical norms may be possible without an accompanying large-scale change in internally held beliefs.

Key references:

Who: Dimitris Xygalatas, IMC (xygalatas@mac.com); Martin Lang, University of Connecticut

What: We will examine the effects of ritualization on anxiety. Since the time of Malinowski (1948), anthropologists have argued that rituals may function to reduce anxiety (Boyer & Liénard 2006; Dulaney & Fiske 1994; Zohar & Felz 2001). Our previous work (Lang et al. forthcoming) showed that inducing anxiety resulted in more ritualized behavior manifested in repetitive hand movements. Yet, the way in which ritualized behaviours might allay anxiety across individuals and social contexts remains unknown. Previous studies used correlational designs that involved second-hand accounts (Fiske & Haslam 1997; Zohar & Felz 2001) or experimental designs that relied on self-reports (Anastasi & Newberg 2008). Moreover, no study has looked at the effects of real-life rituals on anxiety. We will run two studies to investigate these effects in quantifiable ways. The first will be conducted crossculturally in laboratory settings in Eastern Europe and North America. The second will consist of a field experiment looking at real-life religious rituals in Mauritius.

How: We will investigate the effects of repetitive behavior on anxiety. We operationalize repetitive behavior at two levels: movement patterns (experiment 1) and speech patterns (experiment 2). In each experiment, we will collect baseline anxiety measures and induce anxiety by using a public speaking paradigm (Feldman et al., 2004). Subsequently, participants in the experimental condition will either perform prescribed repetitive movements (exp. 1) or read repetitive verses out loud (exp. 2) for 5 min. Controls will perform comparable non-repetitive activity, and participants in the baseline condition will just rest. Heart rate variability (HRV) and galvanic skin response (GSR) will be measured as proxies of anxiety. We predict faster recovery from induced anxiety (indicated by decrease in HRV and GSR) in the experimental condition compared to the other two conditions. In the field study in Mauritius, we will study two naturally occurring rituals (pujas) with different degrees of repetitive body movements and speech patterns, and measure HRV and GSR before, during and after those rituals. Participants will be selected via pre-screening to assure sufficient variability in trait anxiety.

Why: Ritual behaviour constitutes a great evolutionary puzzle, given its ubiquity and apparent lack of utility. Insights about its potential functions may provide valuable answers to this puzzle. Importantly, this project also has potential for clinical applications. A better understanding of some of the mechanisms by which ritualization might soothe anxiety may reveal better ways of stress-management and coping with anxiety. Furthermore, this project builds on several years of work on ritual and long-term ethnographic research by the applicants. It will thus contribute to strengthening a consistent body of research pursued at the IMC since its inception. In addition, it will set the foundations for a broader collaboration with the University of Connecticut, where the main applicant is also affiliated, while strengthening our existing collaborations in Mauritius and the Czech Republic.

What’s next: We expect this grant to do exactly what its name implies: help us develop a broader line of research that will grow and flourish in the future. We intend to continue pursuing this research over the coming years. Results will be submitted to high-impact journals in disciplines like psychology, anthropology, medical science, and/or general science journals. Such results would also strengthen our case for applying for larger grants both in Denmark and in the US (e.g. Velux, NSF) in order to further this research programme.

Additional Comments: Co-funding for this project will be provided by the Experimental Anthropology Lab at the University of Connecticut and by the Laboratory for the Experimental Research of Religion at Masaryk University, who will provide lab space, equipment, and RA support in the USA and the Czech Republic respectively. Portable equipment for the field study is already available at the IMC.

Key references:

Who: Ethan Weed, (ethan@dac.au.dk), Alexandra Kratschmer (romak@hum.au.dk), Andreas Lieberoth (andreas@psy.au.dk), Riccardo Fusaroli (semrf@dac.au.dk)

What: Can we use portable EEG equipment to reliably measure changes in cognitive state in the lab and in the wild?

How: In the lab, we will use portable EEG equipment to measure how state changes in EEG signal correlate with performance on tasks tapping working memory. Previous research has indicated that changes in specific frequency bands (e.g. Näpflin et al, 2008; Palomaki et al, 2012) correlate with changes in working memory load. We will measure EEG while participants rest and engage in working memory tasks with variable degrees of difficulty (e.g. n-back tests). In our analysis, we will use selected features (primarily spectral density measures at different bandwidths and at different electrodes) from the EEG signal to train a machine-learning algorithm to identify working memory engagement in a separate dataset. If this is successful, we will take the project outside the lab, measuring participants’ EEG as they perform a semi-constrained naturalistic task involving varying degrees of working memory. Work will be carried out at the COBE lab facilities.

Why: We want to understand how people interact with each other and with the environment. Until recently, it has only been possible to measure neurocognitive processes in interactive situations in highly artificial lab settings. However, recent advances in technology have created devices that are capable of measuring scalp EEG under more naturalistic settings (Debener et al, 2012). In our previous research, also funded with seed money, we compared a mobile EEG system with research-grade electrodes, and found that the device was capable of measuring simple auditory ERP’s (Weed et al, in review). For mobile EEG to be useful for naturalistic research, we will need to test whether these devices can also be used to monitor more complex brain states, like changes in attention or working memory. There has been some research on this (e.g. Liu et al, 2013), but the majority of mobile EEG research is still focused on more traditional, lab-based paradigms, such as P3 ERP’s. We believe that validation of these devices for detecting more complex brain-state changes is an important next step in moving toward true cognitive EEG in the wild.

What’s next: Field EEG researchers will want to decode noisy data and make inferences about cognitive states. The aim of this research is to take the next step in this direction.

Key references:

Who: Hanna Thaler (hthaler@cas.au.dk), Josh Skewes, Line Gebauer

What: Difficulties of autistic people in emotion perception tasks are often explained by assuming an autism-‐specific lack of sensitivity to facial expressions. As part of this project we aim to test this assumption using a signal detection paradigm. In addition, we propose and test an alternative hypothesis: that these differences may rather be explained by a conservative bias, i.e. by a higher threshold for interpreting and labeling something as emotional. Previous studies using more basic auditory or visual stimuli point towards this interpretation (see Skewes et al., 2014), as well as our first emotion perception study, in which sub-‐ clinical autistic traits predicted bias.

How: Using photos from the well-validated Amsterdam Dynamic Facial Expression Set, we morphed faces of a male person from a neutral expression to expressions of embarrassment or sadness. In the study, subjects will be asked to classify a total of 400 pictures as “neutral” or “embarrassed”(in one run)/”sad”(in the other, counter-‐balanced run).

For predefining “neutral” vs. “emotional” faces we sampled two normal distributions from a set of 1000 pictures per emotion, which overlap in the more ambiguous middle part of the morphing spectrum. It is therefore equally likely that faces from the center are predefined as “signal” or “noise”, which effectively simulates a typical signal detection setup, and also complies with the natural ambiguity of facial expressions. Subjects will also fill in questionnaires measuring alexithymia (Toronto Alexithymia Scale-‐20) and autistic traits (Autism Spectrum Quotient). Level of intelligence will be assessed using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS).

Why: Attributing problems in emotion perception to a lack of sensitivity can often be problematic, because most measures of sensitivity don’t single out a potential influence of bias. A signal detection paradigm can help us to quantify these two measures separately and with considerable statistical power. This is important for the discipline because it will give us a clearer picture of why autistic people experience emotion understanding as a challenge. Autism research is part of an established research strand at IMC, and fits well with the main themes of the research center.

What’s next: Finding additional evidence for our hypothesis could result in an important paper in the field. The results also may serve as a basis for more complex research questions (e.g., considering factors that may influence this bias)

Key references:

Who: Hanna Thaler (hthaler@cas.au.dk), Joshua Skewes, Pete Enticott (Deakin University), Jakob Hohwy (Monash University)

What: This study focuses on vicarious and first-‐person experience of embarrassment during the evaluation of potentially embarrassing photos of oneself and others. It aims to investigate three main questions:

1. Is it more embarrassing to do a self-‐evaluation task together with another person? Does it affect vicarious embarrassment for the interaction partner?

2. Are baseline differences in embarrassment predicted by sub-‐clinical autistic traits? Do these traits moderate social influence?

3. How does stimulation of the dorsomedial PFC via TMS affect embarrassment (for oneself/for the other person)?

How: This study will be carried out in Peter Enticott’s cognitive neuroscience lab at Deakin University. We will test non-‐autistic participants aged 18 to 35. The plan is to adapt an existing task developed by Morita et al. (2008) (see references): In the first part of the studies, we will make videos of participants’ faces while they answer interview questions about their life, short calculus problems, and sing a song. From this video material we will select snapshots of more ‘awkward’ expressions (mouth wide open, eyes half-‐closed, etc.) and snapshots that look as if they pose for a photo. (All of these will be validated by independent judges.) On another day, participants will come in in pairs of two. They will rate attractiveness of face stimuli once alone, and once together with the other participant. We will measure the EEG of one the participants, and apply sham or real theta-‐burst stimulation to the dorsal MPFC. To measure arousal, both participants will undergo pupillometry. Autistic traits will be assessed prior to testing via a web version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient questionnaire.

Why: The study can contribute to our understanding of embarrassment as a social emotion that plays an interesting role in interpersonal interaction. Results could point to new hypotheses regarding how the perception and experience of this emotion might be altered in autism. Moreover, it could pinpoint a causal modulatory role of the dorsal mPFC in vicarious and first-‐person embarrassment. Finally, the focus of this study complements our ongoing research at IMC about autism and emotion perception.

What’s next: This project marks a first collaboration with two research centers in Melbourne, which will benefit from expertise in experimental philosophy and autism research (Jakob Hohwy) and applied methods of cognitive neuroscience (Pete Enticott). We expect to publish interesting results, which will also form a major part of the PhD project of the main applicant.

Key references:

Who: Jakob Arnoldi, jaar@badm.au.dk, Department of Business Administration, AU (main applicant), Kristian Tylén, kristian@dac.au.dk, The Interacting Minds Centre, AU, Pernille Smith, pernille.smith@badm.au.dk, Department of Business Administration, AU, Riccardo Fusaroli, fusaroli@gmail.com, The Interacting Minds Centre, AU

What: How do we deal with decisions in increasingly complex environments? We investigate dyads of participants jointly categorizing stimuli according to increasingly complex patterns (Voiklis 2012). We are interested in which interactional dynamics (e.g. lexical alignment, decision routines, etc.) predict ability to solve the problem and adapt to increasing complexity.

How: We rely on a previously collected corpus of 30 dyads solving the task. We transcribe their interactions at word level and time-code the transcripts. Indexes of lexical and syntactic alignment, as well as of routines are then related to performance in the task and experiences of the interaction (as assessed with IMI questionnaires).

Why: The study offers an insight into effective interaction dynamics for joint problem solving, with a focus on increasing complexity of the task. The findings can be employed to better understand behavioral and cognitive patterns in innovation professionals (a vastly unexplored issue in management and innovation). The study contributes to current research on interacting minds by adding the complexity parameter and developing a paradigm open to further manipulations.

What’s next: The experimental paradigm is open to new manipulations: asymmetry of information between interlocutors; uncertainty in the information available to interlocutors; availability of social information from other deciders.

Key references:

Who: Main applicant: Jens Sand Østergaard Ph.D. Student,, Department of Aesthetics and Communication, AU. norjoestergaard@dac.au.dk, Line Gebauer, assistant professor, Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, BSS, AU, Joshua Skewes, postdoc, Department of Culture and Society, ARTS, AU

What: My proposed project concerns how the language problems associated with three different types of diagnosis for children – autism spectrum disorder (ASD), specific language impairments (SLI) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) – may have common roots in working memory. Although the language profiles characterizing the individual disorders are fairly distinct, there seems nonetheless to be evidence of an overlap of language-specific symptoms between each group: a child diagnosed with ASD might, for instance, show problems with word-repetition, which fits more closely with the impairments found in SLI. To examine whether it is possible to find new means of distinguishing overlapping symptoms, I propose to investigate connections between language functions and models of working memory to examine these differences and similarities and re-assess the description of symptoms.

How: To address my research question, I will draw a preliminary model of how sentences are understood by retrieving and integrating relevant contextual information in working memory, as well how irrelevant or interfering information is suppressed by attention in typical language use. From this model of how connections between language and working memory normally function and with current tests of language (dys)functions, such as the CELF-4, as a point of reference, I wish to put forth hypotheses to explain how the overlapping problems of language functions in ASD, SLI and ADHD may be tested by using dual-task experiments which combine measures of sentence comprehension with aspects of working memory (such as non-word repetition).

With the help of speech and language psychologists at special-needs schools for children with ASD, SLI and ADHD, I wish to examine the viability of this dual-task approach to comorbidity by examining it in relation to single measures of sentence comprehension and WM on the CELF-4, as well as in relation to qualitative reports of children’s language behaviors between the ages of 9-12 through structured interviews with teachers and other specialist staff at these schools.

Why: This project will hopefully provide a preliminary measure of the often heterogeneous nature of language dysfunctions in ASD, ADHD and SLI, which may later serve as a basis for future group comparison studies at the IMC. Further, if successful the project may provide ways of addressing issues of student-specific teaching and class structure at schools for children with receptive and expressive language problems.

What’s next: In addition to publications and conference talks, I hope to use this project as a basis for a future post-doctorate application in which I will attempt to elaborate on present hypotheses and their possible applications in the teaching sector. Further, I hope to stimulate continued collaboration between schools for autism and ADHD and IMC, which may be beneficial for future projects and inquiries, as well as the students attending such schools.

Additional comments: The project will be part of my MSc dissertation at the University of Edinburgh and will be carried out in collaboration with supervisors at the School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences in Edinburgh.

Key references:

What: Investigating novelty detection as the fundamental role in odour memory of everyday life via a choice blindness experiment. In a recently published theory of conscious odour perception (Köster, Møller & Mojet, 2014), it is postulated that our reaction to novel, unexpected odours/flavours takes precedence over our awareness to odours/flavours already known or liked. The theory proposes that odour perception and odour memory are largely implicit, serving to facilitate functional goals for everyday life (e.g. safety). Conversely, conscious olfaction perception is directed towards novelty detection. Only a limited number of studies have tested the main assumptions of the theory – something that this research will address.

How: A variation on the methodology described by Hall, Johansson, Tärning, Sikström and Deutgen (2010) will be used. In their study, Hall et al. (2010) ask participants which item they prefer from two available choices within the same product category (e.g. two jams). Upon presenting the preferred product again to the participant in order to access why the participant prefers the chosen product, the experimenter performs a sleight-of-hand procedure, and presents the non-chosen product. Studies have found only a minority of participants notice the change. The current study would implement a third variant to the second part of the Hall et al. (2010) method. Specifically, using a between-‐subjects design participants would be presented with either (i) the actual chosen product; (ii) the non-‐chosen product; (iii) a new (novel) product from the same category. The theory predicts less choice blindness in the third condition in comparison to the second, due to the influence of novelty detection in odour perception.

Why: Unconscious olfactory processes play an influential role regarding mood, decision-making and choice behaviour (Gaillet-‐Torrent, Sulmont-‐Rossé, Issanchou, Chabanet, & Chambaron, 2014). This has adaptive value, in allowing attention to be directed to potentially dangerous (novel) stimuli. Yet, greater research is needed. By incorporating a choice blindness paradigm, the proposed study explores whether (i) novelty detection is of paramount centrality to olfaction cognition and (ii) whether the outcome of a choice reveals underlying preferences. The study thereby resonates strongly with the IMC cognition, communication and choice directive, and is of interest to psychologists, consumer behaviour researchers, health professionals and economists.

What’s next: The seed is sown for further research by means of a PhD, and possible research collaboration with other universities.

Additional Comments:

Background: I came top of my year studying psychology and then continued my education as a psychology research assistant at Murdoch University, Western Australia, before commencing my MSc Sensory Science at Copenhagen University in collaboration with Wageningen University. Seed funding is to aid young and motivated researchers and I welcome the opportunity to integrate research activities with my daily COBE Lab duties.

The current research project:

The project tests a key assumption of conscious odour perception, which is a fundamental tenet to human perception, memory and everyday living. However, psychological aspects of olfaction have been unrepresented in academic papers (Keller, 2011; Smeets & Dijksterhuis, 2014), and as a result, how the brain integrates such perception to a multi-‐sensory level is still in infancy (Auvray & Spence, 2008; Stevenson, 2014; Zucco, 2012). Furthermore, consumer testing is often reliant on introspection and self-report (Hall et al., 2010).

I have been in personal communications with E.P. Köster and Per Møller, the first and second author of the theory described above. Both researchers taught me during my MSc. Per has strong research communications with Aarhus University, in particular research collaborations with Joachim Scholderer – a board member of COBE Lab. There is thus great potential, not only at the inter-‐disciplinary level, but also on a national footing, to enhance network connections. This can be achieved by designing future studies (e.g. initiating a PhD) that develop upon strong theoretical grounds, which this study purports to examine.

Method:

Due to an element of deception being used, participants will be recruited through the CFIN participant pool. Experimental sessions will take place at either COBE Lab, or at an external venue. As in the method of Hall et al. (2010), a second researcher will be required to perform the study, and therefore a research assistant will be employed. A between subjects design will be used, with one of the three conditions presented in a randomised order. Two hundred participants will be recruited, and considering the study to take no more than ten minutes, a voucher of value 30 DKK will be issued.

Publication and dissemination:

The paper is to be submitted to either the Journal of Sensory Science or Food Quality and Preference, with a poster submitted to the leading sensory science conference (Pangborn), held in Gothenburg in 2015.

References:

Who: Joshua Skewes, Lene Aarøe, Michael Bang Petersen

What: Generally, how does a person's life history affect basic cognitive processing? People are deeply shaped by their life history, and are fundamentally historical beings; however life history has been ignored by cognitive scientists. We wish to continue our groundbreaking research in methodologically rigorous cognitive science that is sensitive to life history.

We are currently finishing up our previous seed funded project on life history and its effects on perceptual capacity and attention. The question here was, how does growing up in a harsh and unpredictable environment shape basic perceptual and cognitive functions? We would now like to examine whether cognitive differences are also tied to differences in learning style.

We would like to test whether people from difficult backgrounds are worse at suppressing/ignoring redundant/uninformative cues. Think of Pavlovs dog. Imagine the dog has learned perfectly that a bell predicts food. The dog will salivate maximally to the bell whenever it is presented. Now imagine that we add a light to the stimulus. Because the bell predicts the food perfectly, there is nothing left for the light to predict, and therefore nothing left to learn. So formal learning theory predicts that when you test the light alone later, the dog will not salivate to it, even though it has been paired with the food. Put succinctly, there is no prediction error left for the light to explain, because the bell explains everything, so the light is redundant and uninformative. This phenomenon is called Kamin blocking.

Following on from our attention study and the general idea that people from difficult backgrounds are more open to information because they have developed in a more chaotic context, we predict that this Kamin blocking effect would be reduced. This is because if life has been chaotic, you could never really feel safe that information was redundant (i.e. cognitive hyper-vigilance). In line with our other study, this would also be part of a cognitive style that has its disadvantages and advantages dependent on context. This cognitive style would be characterized by difficulties in filtering out task irrelevant information (currently funded attention study), which would lead to a decreased inability to suppress redundant/uninformative information in learning.

How: Harshness and unpredictability of life history will be quantified using a life history questionnaire developed in Michael and Lene's lab. Kamin blocking will be quantified using a new perceptual blocking task developed in our autism group. Life history measures will be regressed against blocking measures, to determine which elements of life history predict individual differences in learning style.

Why: This is important to the talent development of Josh and Lene, because it could become a key area of collaboration, and a topic to focus on in applying for joint funding (along with Michael) to further develop as PIs. This research is important to the discipline because knowledge of life history constitutes a major epistemological gap within cognitive science, while at the same time, better knowledge of basic cognitive functions would greatly enhance the state of the art in political science. This is important to the centre because it further strengthens true collaborations between the social scientific and humanistic arms of IMC, in which both disciplines are represented equally in terms of workload and scientific input. Thus this project strengthens the interdisciplinary profile of IMC. At the same time, the project fulfills the promise made in the centre application to contextualize models of cognition in the social/developmental history of agents. This is important for the world, because individual differences in life history and its effects on cognitive performance are under investigated in research, and underdefined in educational contexts. One application of our research could be better identification of strengths and weaknesses in the classroom that result from differences in life history. Thus, over time and applied in the right way, our research may have important pedagogical consequences, and may suggest ways that class activities can be structured to enable greater access to equal opportunities for students from all backgrounds.

What’s next: Following on from our attention study, we expect our results to be publishable, with potential papers in cognitive and political science. If successful, this research could set up a larger application (FKK or TRYG) on the influence of life history on cognition to be submitted by Josh, Lene, and Michael. Lines of research that we are discussing include clinical applications in PTSD, clinical research on adults who have grown up in families of addiction (i.e. Eugene Raichle’s notion of ecologies of addiction), and research on other features of life history.

Additional Comments: To get sufficient variability in peoples’ life history, particularly harshness/unpredictability of upbringing, we will need to recruit people from outside of the university to participate – because students will be more likely to come from a uniformly high SES background, and so have a more uniform life history. And to get enough subjects to run the correlational design we require to run in order to investigate the relationship between life history and cognition, we will need 100 such subjects. We are applying for RA assistance for this purpose. The paradigm will take about 20-30 minutes to run, and we can run up to six subjects in parallel, but we have budgeted 1 hour RA time per subject to cover time required for recruiting and admin.

All participants will be processed through the COBElab subject pool, so that investment in this project will have a spill-over effect there. Not only will we be broadening the pool in terms of number, but we will be enhancing the generalisability of the sample and thus benefitting everybody connected to IMC/COBElab. This strategy has been very successful for our attention study.

Who: Joshua Skewes, Line Gebaur, Katrine Filtenborg, Hanna Thaler

What: We propose to conduct research investigating whether the known perceptual bias of autistic people towards sensory details has any consequences for how autistic children and autistic adults learn about complex stimuli.

How: We will run our study on separate ASD and neurotypical groups of children and adults. So we are applying for two separate studies within the same project.

We will ask participants to perform a Kamin blocking task. Kamin blocking is a conditioning phenomenon whereby learning of an association between a cue and an outcome reduces learning of associations for new cues. Imagine that Pavlov’s dog has been trained to salivate to a bell by pairing it with presentation of food. Now imagine that a light is added to the bell. Adding the light will make no difference for salivation, because the bell already fully predicts the food. The light adds no information, and hence the dog doesn’t attend to it, and doesn’t learn its relevance to food.

We will conduct an experiment using this same basic structure, but instead we will replace bells and lights with child friendly shapes and colors. The standard way to conceive of such pairings of multiple cues – of lights and bells – is as compound stimuli. If a detailed processing style in autism has consequences for learning, then it might be because autistic children are better at resolving compound stimuli into their stimulus components (i.e. details). Thus, for autisitic children, we might expect reduction in blocking effects. This would be evidence of a detail focused learning style, which we believe underlies perceptual and social/communication symptoms of autism.

Why: This experiment is important to our group because we are interested in applications of our basic research to real world contexts. This experiment extends our ideas about perception to learning in children, and thus is relevant to applied pedagogy. This experiment is important to the centre because it marks the beginning of what we hope will be a continuing collaboration with autism centers in Funen and Vestsjælland, which will allow for an increase in our network for applying IMC themes in clinical contexts. This experiment is important to the discipline because it extends knowledge of autistic perception to the potential discovery of new phenomena in autistic learning styles, and helps extend our model of autism (which we have used to successfully explain perceptual and social differences associated with autistic traits) to new understanding in learning. This is important for the world because it may have implications for teaching autistic children and for life-long learning in adults.

What’s next: Results from learning studies will demonstrate the real world applicability of our research, which will strengthen our ongoing applications to the ERC, NIMH, FKK, and Lundbeck. Any results available for upcoming funding deadlines will be included in ongoing applications as pilot data. The project will also be a first step in a longer term collaboration with centers in Fyn and Vestsjælland. The work will be easily publishable, even if we get null results, as people are very interested in learning styles in autism, and surprisingly little rigorous work on learning in autism exists. The work will lead to two separate papers, as the adult and child data will need to be published separately.

Additional Comments: A similar application to this one was submitted last year, but the money was never used because our Syddansk collaborators were delayed in running their test battery. To solve this problem, Line has secured our own autism samples (both children and adults) at centers on Fyn and Vestsjælland, and so we will be running most of our testing there. The participants have not had any psychometric testing (IQ, diagnosis verification etc), so we will need to do all of that too. This means that it will only be possible to test at most 2 participants per day. As such, the travel expense is disproportionally high because Line and Katrine (Line’s intern and RA) will need to travel back and forth to run psychometric testing and the batteries. However, the expense ends up being much less than if we were to contract a local psychologist to do the testing, and Line would like the opportunity to spend more time at the centers. Plus, once tested, we will be able to return to the centres and re-use the samples in future studies, where we can be more efficient (i.e. test more participants per day).

Who: Karsten Olsen, karsolsen@gmail.com (IMC, CFIN), Andreas Roepstorff (IMC, supervisor), Kristian Tylén (IMC, CfS), Dan Bang (Oxford)

What: This project aims to develop further our existing experimental paradigms that includes more than one person in the lab – for the purpose of investigating the role of social interaction, different channels/media of communication, and other factors. In particular, the project will explore how the opportunity to interact linguistically with others in an experimental setting may differently affect learning, decision-making, and other cognitive domains.

These investigations constitute follow-up experiments on previously published studies, control experiments for current on-going studies, and pilots for future research. Common for all of them is the need to develop better experimental designs for, and to zoom in on, the processes that are involved when individuals interact with others and how this situation may modulate their perception, learning, and other cognitive abilities.

How: The project will build on existing experimental methods (see Bahrami et al., 2012; Bang et al., 2014; Fusaroli , Rączaszek-Leonardi & Tylén, 2014), using only stimulus computers for behavioural experiments which will take place in the COBE lab.

The experiments will usually take two hours incl breaks. To reach sufficient statistical power, we plan approx. 15-30 pairs (30-60 individuals) of participants, depending on whether we investigate data from both or just one member of the pair. For pilot studies we plan approx. 5 pairs (10 individuals). Over the course of the next year, we plan about 5 pilot experiments and 5 full experiments, including own and course-related data collection (see below).

Why: The theoretical and experimental research that builds on interactive experimental designs is still very recent and modest, and there are still many underspecified and unresolved questions. In order to move forward, we need to develop the proper methodology to test the predictions of the theoretical work and to answer satisfactorily the questions of what role social interaction plays in human behaviour, cognition, and culture. In particular, while allowing individual to interact, this project will using rigorous methods from psychophysics and signal detection theory in a laboratory setting, because strict experimental control is needed to alleviate the many variables emerging from free social interaction.

What’s next: As previously in this line of research, this project will produce a number of publications, while also forming a basis for a number of new collaborations across Aarhus and Oxford, as well as previous collaborators.

Additional Comments: Not only will the advancement of interactive experimental paradigms (and the published papers) increase our understanding of interactive behaviour and cognition, we will also attempt to educate and inspire students to increase their understanding of research on interacting minds. We aim to include also a number of our pilot studies as part of the teaching of two courses at AU, which will involve the students in theoretical and empirical research, and in performing an interactive experiment (under supervision). The courses are “The role of linguistic interaction in learning and cognition: An introduction to experimental approaches” (lectured by K Olsen) and Research Workshop: "Experimental Semiotics: Investigating the Emerge of Novel Sign Systems" (lectured by K Tylén and K Olsen). By introducing the students to the basics of interactive experiments, we aim to inspire and encourage future endeavors into the study of processes emerging between interacting minds, and the use of more ecologically valid paradigms to study them.

Key references:

Who: Kristian Tylén (kristian@cfin.dk), Riccardo Fusaroli and Gregory Mills (University of Edinburg)

What: Recent advances in the psycholinguistics of dialogue raise fundamental questions concerning the individual and collective cognitive processes involved in linguistic interaction. To which extend are these processes attributable to the individual interlocutors and to which extend are the rather an emergent property of the interaction? What is the role of anticipatory dynamics, prediction, feedback and repair? We will try to approach these questions by creating an experimental situation where participants are led to believe that they are changing communicative partner when they are not or change partner when they believe to be continuing with the same partner. Using a number of measurements, we will investigate how and to which degree dialogical coordination is disrupted/facilitated through five different conditions.

The hypothesis is that target situations of conflict will be indicated by disruption of typing speed, less lexical variation in expressions of confidence, and more moments of repair.

How: Integrating the by-now well known ‘optimal-interacting-minds’ paradigm (Bahrami et al., 2010; Fusaroli et al., 2012) with a network-based chat tool (Mills, 2011) allows us to manipulate participants’ knowledge of who they are communicating with on various points in time. It also allows us to bypass the huge transcription bottleneck experienced in earlier versions of the paradigm since all interactions will be typed and stored with the chat tool. We plan to include participants in groups of 32 organized in small networks of 4 each assigned to one of four conditions making up a 2-way between quadrant factorial design. The factors are actual (physical) change of communication partner (+/-) and apparent change of communication partner. The experiment will be run relying on the computer lab at COBELab (recruitment or deceptive conditions will however happen through the CFIN SONA) and pilot testing has already been completed.

Why: There is a huge interest in the relation between predictive models of cognition/brain and social coordination. This experiment systematically manipulates participants’ expectations creating moments of top-down and bottom-up conflicts (prediction-errors). We thus expect to make an important contribution to ongoing discussions both in the predictive-models and dialogue community.

What’s next: The paper resulting from this experiment will be submitted for publication in a high-profile journal. It also allows for numerous further manipulations, several of which are already on the sketch board. Besides, the integration of the optimal interacting minds paradigm with the chat tool lends itself as a valuable tool for other research projects within as well as outside IMC.

Additional Comments: Notice that we have previously applied for the same (or an earlier version of this) project. However, the project was unfortunately delayed. We have now made a number of improvements to the design, it is already implemented in the computer lab at COBE and we will be running the first batch of participants on Monday dec. 1st 2014.

Key references:

Who: Assistant professor Lars A Bach, Interacting Minds Centre, Arts, AU. (mail: lbach@cas.au.dk). Professor Trine Bilde, Social spider group, Bioscience AU. (mail: trine.bilde@biology.au.dk) post doc Maria Abou Chakra, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology, Plön, Germany. Postdoc Christian Hilbe, Program for evolutionary Dynamics, Harvard University, USA.

What: An example of symbolic punishment in social interaction is the rating of other interaction partners in the social media like AirBnB, Ebay and others. This work is on the interface between evolutionary bioscience, experimental psychology and behavioural economy.

How: This project will be conducted as a combination of modelling and of experiments on human choice. In other words we are going to design an experimental design to test how human subjects make use of the possibility of symbolic punishment. This will be conducted in the COBE Lab. In addition we will design models to investigate the evolutionary stability of different strategies within an ecology allowing for symbolic punishment and behavior conditioned on the ‘standing’ or symbolic reputation of the interaction partner.

Why: the relevance should be apparent from the increasing use of social media to mediate human interaction and therefore increased use of some kind of reputational system. The basic and evolutionary plausible human behaviour in such a setting is fundamental for the understanding of large scale human interaction.

What’s next: The projects should generate publishable results publications both in terms of experiments and in terms of modelling. Finally, sustained collaboration with Max Planck and Harvard University may be advantageous on the long run.

Key references:

Hilbe, C., Abou Chakra, M., Altrock, PM., Traulsen, A. (2013) The Evolution of strategic timing in collective-risk dilemmas. Plos ONE 8(6): e66490. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066490

Who: Main applicant: Marc Andersen, AU (mana@teo.au.dk); Relevant coworkers: Uffe Schjødt, AU (us@teo.au.dk), Kristoffer L. Nielbo, AU (kln@teo.au.dk) & Jesper Sørensen, AU (jsn@teo.au.dk), Andreas Roepstorff (andreas.roepstorff@cas.au.dk); International coworkers: Thies Pfeiffer

What: We wish to conduct a study on prediction, perception and agency in closely coordinated action by studying volunteer participants playing on a Ouija Board. Through two rounds of seed funding, we have now successfully constructed four sets of eye trackers and bought four computers to handle the software. We are now ready to conduct the planned experiment. We now apply for additional SEED- funding to pay participants.

How: Experiment: Volunteer participants in groups of two will be equipped with home build low-cost eye trackers, hand accelerometers and heart rate monitors while playing on a Ouija board. After playing participants will answer a questionnaire with questions about feeling of control, perception of other players, and personal experience with the game.By measuring eye-gaze and hand movement we predict that

1) the eye-gaze of one or more individuals will predict the direction of the planchette on the Ouija board,

2) the more individual share visual orientation the faster the planchette will move,

3) experienced individuals will have greater influence on the planchette, and 4) the closer the group is coordinated the greater the perception will be that agency lies outside of the group.

Why: Predictive coding has recently established itself as the dominant paradigm for understanding perception and action (Frith 2007, Bar 2009, Friston & Kiebel 2009). More recently predictive coding has also been used in cognitive models accounting for sense of agency (Friston 2012). However, the relationship between prediction, perception and agency attribution in closely coordinated actions has not yet been much examined, and could potentially lend fascinating insights into basic human cognition, interacting minds and group dynamics.

What’s next:

a) Collaboration with eye tracking lab in Bielefeldt, Germany. b) After this experiment we have hopefully gained new knowledge and expertise with the equipment, which can then be easily implemented in other research paradigms.

Key references:

Who: Mikkel Wallentin, mikkel@dac.au.dk; Kenny Coventry, University of East Anglia

What: Does embedding in left-hand vs right-hand traffic influence cognition in a similar way that reading direction does?

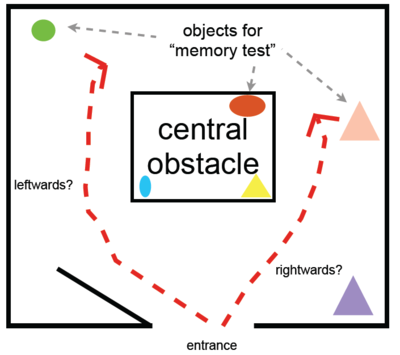

How: In the “room inspection task”, developed by MW, participants go through a room and around a central obstacle in what they believe is a memory experiment. In two pilot experiments (unpublished) it was found that participants are biased towards going around the obstacle rightwards (see figure below), in concordance with right-hand traffic rules in DK. In the latest experiment, 218 participants were tested, 70% chose a rightwards path (Chi-sq(1)=30.5, P<0.0001). No effect of handedness was found. In the current experiment, we will make a more standardized replication of the findings from the Danish population and investigate if a sample from a left-hand driving culture (UK) displays a reversed bias. The experiment will include a memory experiment in which we will investigate if object location may be a predictor of recall differences between the two sample groups.

<strong>Why: Lateralization in language processing and dexterity are known causes of behavioral bias (Wallentin, et al., 2014), but an increased focus on culturally based biases are emerging (e.g. Chatterjee, 2001; Fuhrman & Boroditsky, 2010; Santiago, et al., 2007; Winawer, et al., 2007). It is important for cognitive science to disentangle and quantify the effects of these different elements (Coventry, et al., 2014). This can only be done by cross-cultural comparison.

What’s next: This experiment is a part of an ongoing collaboration between MW and KC. Given that we have already twice shown a clear behavioral bias in the Danish sample, the results of the cultural comparison should be publishable, regardless of the results (A difference shows a bias from culture, whereas a lack of difference indicates a more “cognitive” origin). We aim at publishing the results in PLOS One.

Additional comments:

In the experiment, participants are told that we are investigating how movement affects memory performance. They are asked to enter the experimental “maze” and take one round there in order to encode as many of the objects as possible. They are asked not to stop at any point and they are given a fixed amount of time to walk through the “maze”. Afterwards, their memory is probed for which object they remember, and number of recalled central/peripheral objects are used as dependent variables together with walking direction. An interaction between walking direction and object location during recall is expected, due to attentional and movement bias. Furthermore, we expect to see a difference between participants from the DK and UK groups in both recall bias and walking direction.

Key references:

Who: Oana Vuculescu, omvuc@asb.dk, BSS, Carsten Bergenholtz, cabe@asb.dk, Jacob Sherson, sherson@phys.au.dk

What: The overall aim is to attempt to investigate social learning and (near-) optimal timing for information revealing in groups– i.e. when should an individual trying to solve a problem have access to information from other individual solvers such that fixation effects are limited on the one hand and positive changes in problem representation occur more frequently, on the other.

How: An already existing hierarchical game will be further developed and tested in different contexts, while also introducing a new time-dimension, i.e. the study not only investigates the influence of social learning but when (during the problem solving process) is social learning most beneficial. While the actual design and layout may change, we want to build on the hierarchical toy problem since it allows the identification of distinct problem representations as well as changes in problem representation as a result of social interaction. As an intermediate step, several online experiments will be conducted using MTurk offering a crucial refinement for both design and hypotheses. The enrollment of a game developer as well as several “robustness checks” that will be carried out on MTurk aim to insure that the game design and other variables (e.g. incentive or reputation systems (Dellarocas 2010)) do not have a significant (potentially) confounding effect on the main dependent variable. Although studies suggest that MTurk experimental data is reliable (Kittur, Chi et al. 2008; Mason and Suri 2012), given the particular experimental-set-up (i.e. the game as a unique solution) the final hypotheses testing needs to be carried out in the relatively controlled environment of the COBE lab. All manipulations are between subjects with a total of 300 participants.

Why: This project is designed with several goals in mind: 1. Robustness checks for previous results i.e. showing that they are not contingent on exogenous factors such as website layout, game design etc. 2. Introduce a time dimension as well as a contingency element to our previous study. As such, social learning is beneficial since solvers are often able to learn faster a better problem structure and solve a problem more efficiently, but they are also likely to fixate on peers’ contributions. Our working hypothesis is that fixation effects could be successfully mitigated if solvers do not have access to other solutions during early phases of CPS. 3. The lessons learned in this study will find application for the optimal incorporation of social learning in collective problem solving platforms such as Science at Home.

What’s next: These experiments are the first step to being able to perform massive tests on the science at home platform.

Additional comments and references

Fixation is a well- documented phenomenon in problem solving (Smith and Blankenship 1991), that has gathered little attention in the recent literature concerning collective problem solving or crowdsourcing for innovation. So far, the literature concerning online CPS has fixated (sic!) on fixation effects within individuals (i.e. fixation due to past success (Bayus 2013)). In line with cognitive science literature, the current project focuses on the potentially more pervasive effects of fixation that occur due to solvers’ exposure to other people’s solutions. The goal is to study fixation in larger groups of solvers using a dynamic perspective which seems to be lacking – i.e. most studies focus exclusively on the output (Chrysikou and Weisberg 2005), rather than the process itself.

Who: Panagiotis Mitkidis (PI – mitkidispan@gmail.com), Christopher Kavanagh*, Abhisek Kumar, Shuhei Tsuchida, Robert Thomson, Bijar Ghafouri, Eduardo Castrillon, Harvey Whitehouse, Andreas Roepstorff *equal contribution

What: Rituals are interesting phenomena in themselves. They entail excessive costs, i.e. mental and physical energy and pain, without apparent equal benefits - an evolutionary mystery (Irons, 2001). And they do so in the context of religions, perhaps the most powerful institutions of this world, often involved in social segmentation and conflict.

Cooperative behavior describes individuals contributing their own resources in order to benefit a bigger group as a whole (Rand et al. 2009; Tomasello, 2009; Mitkidis et al. 2013). In the current times of unequal distribution of goods, as well as prevailing religious and political conflicts, exploring prosocial behavior is pertinent. However, cooperative behavior is risky as its outcome depends on the cooperation of others.

Personal commitment can easily fail if: a) Too few people are contributing or b) Free- riders, i.e. selfish or corrupt individuals, take advantage of the altruism of others while destroying the common-good pools. In fact, the traditional economic approach evaluates these risks as so high that it predicts the dominance of selfish behavior over cooperative (Hardin, 1995). The ability to participate in cooperative tasks necessarily depends upon trust, that is, commitment to the other participants for the achievement of collective goals (Axelrod & Hamilton, 1981; Rand & Nowak, 2013).

Fortunately, experience and research have shown that this prediction is too pessimistic. In the real world, as well as in experiments about social dilemmas, people do not always act purely selfish but instead display a variety of prosocial behaviors (Ostrom & Walker, 1991; Fehr & Gächter, 2000; Ariely, 2008). This raises the question: under which precise circumstances do we trust each other and behave cooperatively?

Previous research on the topic has shown that prosocial behavior is, inter alia, fostered by: a) Belief in the group (Gächter et al. 2004) and b) Personal effort employed as time, strain or pain (Olivola & Shafir, 2013). Extreme religious rituals build on both of these themes through community members engaging in excessively painful procedures. Research, specifically investigating the relationship between ritual and prosocial behavior, observed that donations (i.e. prosocial acts) increase as one’s engagement in a ritual increases (Xygalatas et al. 2013). Also, researchers have shown that sharing painful experiences (in lab conditions) with other people promotes bonding and cooperation (Bastian et al. 2014). Nevertheless, more recent research has showed that the picture is not as clear as initially thought; painful rituals do not do only one thing, namely increasing prosocial behavior, but rather activate different (cleansing and licensing) mechanisms to (actors vs. observers) participants, indicating that the route to morality is not a one-way street (Mitkidis et al. in prep).

Corroborating lab research has suggested that pain itself is enough to activate pro- social attitudes (Bastian et al. 2014), significantly higher than those found through placebo effects, and this is followed by the effects of empathy mechanisms, mediated by specific hormonal modulations (Mitkidis et al. in prep).