It takes two to lie

Unique signatures of deception in the way people adjust to each other’s head movement and speech

Link to article at videnskab.dk here (in Danish)

Traditionally we search for signs of deception in the deceiver’s behavior. Using a novel approach for eliciting and detecting deception in naturalistic conversations, a new study finds that deception and conflict can be spotted from the speech and movement that both interlocutor share with each other. Deceiver and deceived become more coordinated, nodding more in unison and adopting a more similar speech rate than in truthful conversations. The paper reporting these findings – “Conversing with a devil’s advocate: Interpersonal coordination in deception and disagreement” – was recently published in Plos One.

The study

“From disguising one’s romantic interest in someone just met, or commenting on how much you like a friend’s unfortunate fashion choice, deception pervades everyday conversations and often goes undetected.” states Nicholas Duran - lead author of the study and assistant professor at Arizona State University. Most studies focus on whether you can detect lies in the deceiver’s behavior. “We were more interested in the social life of deception.” explains Riccardo Fusaroli - co-author and associate professor in Cognitive Science at the Interacting Minds Center, Aarhus University - “As people lie within conversation, what does that do to the ongoing patterns of social coordination? People regularly adjust to each other’s movement and speech. Does deception break this patterns? Or more interesting, do deceivers hijack the coordination process to be more effective in their lies?”.

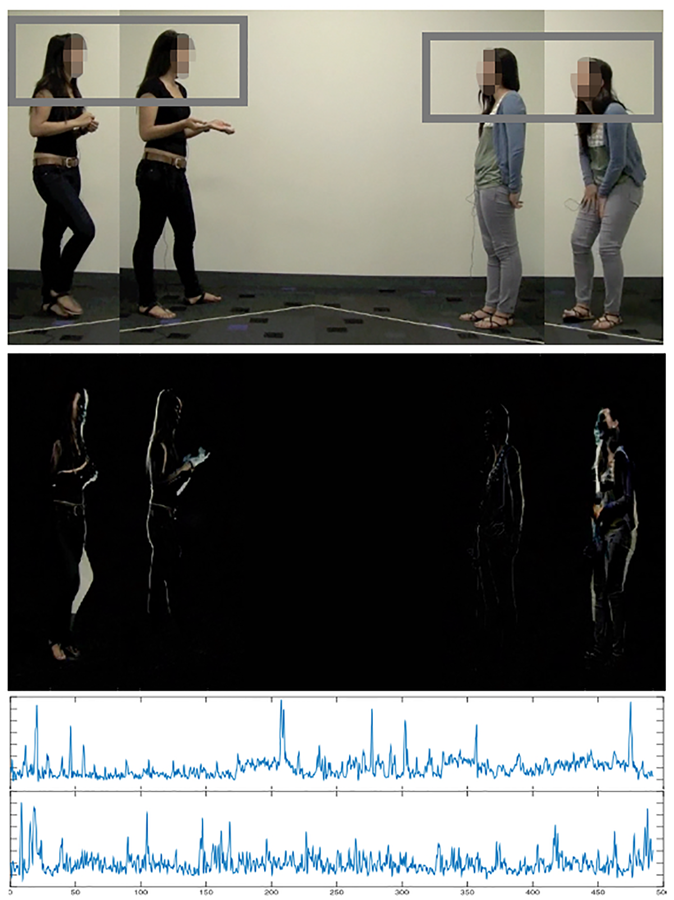

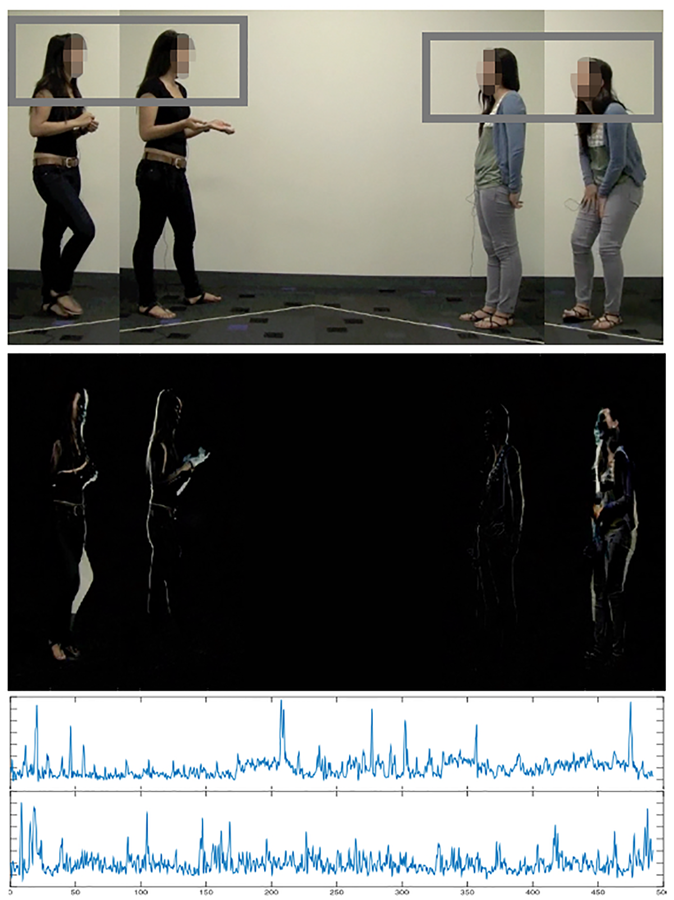

The researchers used a novel “devil’s advocate” paradigm. Participants were brought together to discuss their opinions on controversial topics, like abortion, gay marriage, and drug legalization. Then, in secret, one of the participants was instructed to argue for an opinion opposite to what they really thought. Sometimes their partner also shared this deceptive opinion (where they agreed), and other times they did not (where they disagreed). “We focused on “micro-behaviors”: the moment-by-moment subtle fluctuations in head movement and speech that are measured on the scale of tens of milliseconds” reports Nicholas Duran “We are rarely aware of how our behaviors change and adapt to our interlocutors, often at quite fast rates, but previous research has shown how important micro-behaviors are for social interactions. We rely on them to implicitly judge how much we like each other, to diffuse conflict, and to establish and maintain a wide range of social relations”.

The results show conversations involving deception display a higher degree of interpersonal coordination: people tend to nod and move their heads more in unison, and their speech rate is more coordinated than in truthful conversations. “Usually coordination is taken to be a sign of a well functioning truthful and comfortable social interaction.” elaborates Riccardo Fusaroli “ Here we show that coordination is more complex than that. We might use it strategically to achieve deception, to diffuse a potentially conflictual situation and even to escalate it”.

New insights

The “Conversing with a devil’s advocate” study opens a new window on deceptive and conflictual social interactions and the way we navigate and implicitly negotiate them. It suggests that the deceiver is only a partial entry into the complex social phenomenon of deception, since their behaviors resonate and tightly integrate with those being deceived.

To read the paper

Duran ND, Fusaroli R (2017) Conversing with a devil’s advocate: Interpersonal coordination in deception and disagreement. PLoS ONE 12(6): e0178140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178140

Contact

Associate Professor Riccardo Fusaroli, School of Communication and Culture and IMC